Creating Things

Objectives

- Create a directory hierarchy that matches a given diagram.

- Create files in that hierarchy using an editor or by copying and renaming existing files.

- Display the contents of a directory using the command line.

- Delete specified files and/or directories.

We now know how to explore files and directories,

but how do we create them in the first place?

Let’s go back to Nelle’s home directory,

/users/nelle,

and use ls -F to see what it contains:

$ pwd

/users/nelle

$ ls -F

creatures/ molecules/ pizza.cfg

data/ north-pacific-gyre/ solar.pdf

Desktop/ notes.txt writing/

Let’s create a new directory called thesis using the command mkdir thesis

(which has no output):

$ mkdir thesis

As you might (or might not) guess from its name,

mkdir means “make directory”.

Since thesis is a relative path

(i.e., doesn’t have a leading slash),

the new directory is made below the current working directory:

$ ls -F

creatures/ north-pacific-gyre/ thesis/

data/ notes.txt writing/

Desktop/ pizza.cfg

molecules/ solar.pdf

However, there’s nothing in it yet:

$ ls -F thesis

Let’s change our working directory to thesis using cd,

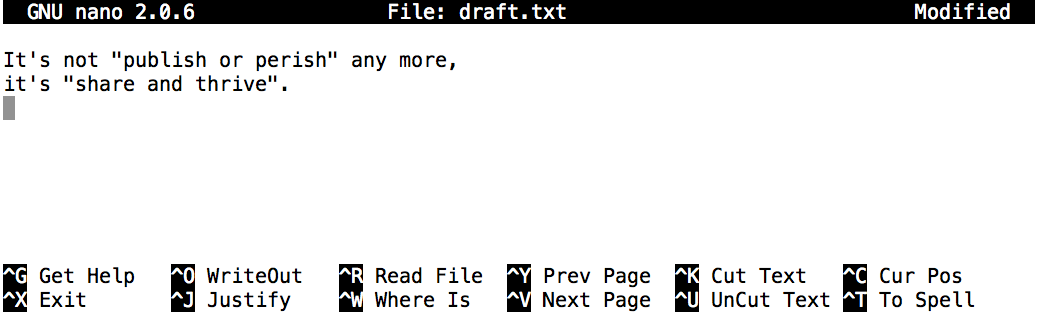

then run a text editor called Nano to create a file called draft.txt:

$ cd thesis

$ nano draft.txt

Which Editor?

When we say, “

nanois a text editor,” we really do mean “text”: it can only work with plain character data, not tables, images, or any other human-friendly media. We use it in examples because almost anyone can drive it anywhere without training, but please use something more powerful for real work. On Unix systems (such as Linux and Mac OS X), many programmers use Emacs or Vim (both of which are completely unintuitive, even by Unix standards), or a graphical editor such as Gedit. On Windows, you may wish to use Notepad++.No matter what editor you use, you will need to know where it searches for and saves files. If you start it from the shell, it will (probably) use your current working directory as its default location. If you use your computer’s start menu, it may want to save files in your desktop or documents directory instead. You can change this by navigating to another directory the first time you “Save As…”

Let’s type in a few lines of text, then use Control-O to write our data to disk:

Once our file is saved,

we can use Control-X to quit the editor and return to the shell.

(Unix documentation often uses the shorthand ^A to mean “control-A”.)

nano doesn’t leave any output on the screen after it exits,

but ls now shows that we have created a file called draft.txt:

$ ls

draft.txt

Let’s tidy up by running rm draft.txt:

$ rm draft.txt

This command removes files (“rm” is short for “remove”).

If we run ls again,

its output is empty once more,

which tells us that our file is gone:

$ ls

Deleting Is Forever

Unix doesn’t have a trash bin: when we delete files, they are unhooked from the file system so that their storage space on disk can be recycled. Tools for finding and recovering deleted files do exist, but there’s no guarantee they’ll work in any particular situation, since the computer may recycle the file’s disk space right away.

Let’s re-create that file

and then move up one directory to /users/nelle using cd ..:

$ pwd

/users/nelle/thesis

$ nano draft.txt

$ ls

draft.txt

$ cd ..

If we try to remove the entire thesis directory using rm thesis,

we get an error message:

$ rm thesis

rm: cannot remove `thesis': Is a directory

This happens because rm only works on files, not directories.

The right command is rmdir,

which is short for “remove directory”.

It doesn’t work yet either, though,

because the directory we’re trying to remove isn’t empty:

$ rmdir thesis

rmdir: failed to remove `thesis': Directory not empty

This little safety feature can save you a lot of grief,

particularly if you are a bad typist.

To really get rid of thesis we must first delete the file draft.txt:

$ rm thesis/draft.txt

The directory is now empty, so rmdir can delete it:

$ rmdir thesis

With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

Removing the files in a directory just so that we can remove the directory quickly becomes tedious. Instead, we can use

rmwith the-rflag (which stands for “recursive”):$ rm -r thesisThis removes everything in the directory, then the directory itself. If the directory contains sub-directories,

rm -rdoes the same thing to them, and so on. It’s very handy, but can do a lot of damage if used without care.

Let’s create that directory and file one more time.

(Note that this time we’re running nano with the path thesis/draft.txt,

rather than going into the thesis directory and running nano on draft.txt there.)

$ pwd

/users/nelle

$ mkdir thesis

$ nano thesis/draft.txt

$ ls thesis

draft.txt

draft.txt isn’t a particularly informative name,

so let’s change the file’s name using mv,

which is short for “move”:

$ mv thesis/draft.txt thesis/quotes.txt

The first parameter tells mv what we’re “moving”,

while the second is where it’s to go.

In this case,

we’re moving thesis/draft.txt to thesis/quotes.txt,

which has the same effect as renaming the file.

Sure enough,

ls shows us that thesis now contains one file called quotes.txt:

$ ls thesis

quotes.txt

Just for the sake of inconsistency,

mv also works on directories—there is no separate mvdir command.

Let’s move quotes.txt into the current working directory.

We use mv once again,

but this time we’ll just use the name of a directory as the second parameter

to tell mv that we want to keep the filename,

but put the file somewhere new.

(This is why the command is called “move”.)

In this case,

the directory name we use is the special directory name . that we mentioned earlier.

$ mv thesis/quotes.txt .

The effect is to move the file from the directory it was in to the current working directory.

ls now shows us that thesis is empty:

$ ls thesis

Further,

ls with a filename or directory name as a parameter only lists that file or directory.

We can use this to see that quotes.txt is still in our current directory:

$ ls quotes.txt

quotes.txt

The cp command works very much like mv,

except it copies a file instead of moving it.

We can check that it did the right thing using ls

with two paths as parameters—like most Unix commands,

ls can be given thousands of paths at once:

$ cp quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

$ ls quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

To prove that we made a copy,

let’s delete the quotes.txt file in the current directory

and then run that same ls again.

This time it tells us that it can’t find quotes.txt in the current directory,

but it does find the copy in thesis that we didn’t delete:

$ ls quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

ls: cannot access quotes.txt: No such file or directory

thesis/quotations.txt

Another Useful Abbreviation

The shell interprets the character

~(tilde) at the start of a path to mean “the current user’s home directory”. For example, if Nelle’s home directory is/home/nelle, then~/datais equivalent to/home/nelle/data. This only works if it is the first character in the path:here/there/~/elsewhereis not/home/nelle/elsewhere.

Key Points

- Unix documentation uses ‘^A’ to mean “control-A”.

- The shell does not have a trash bin: once something is deleted, it’s really gone.

- Nano is a very simple text editor—please use something else for real work.

What is the output of the closing ls command in the sequence shown below?

$ pwd

/home/jamie/data

$ ls

proteins.dat

$ mkdir recombine

$ mv proteins.dat recombine

$ cp recombine/proteins.dat ../proteins-saved.dat

$ ls

Suppose that:

$ ls -F

analyzed/ fructose.dat raw/ sucrose.dat

What command(s) could you run so that the commands below will produce the output shown?

$ ls

analyzed raw

$ ls analyzed

fructose.dat sucrose.dat

What does cp do when given several filenames and a directory name, as in:

$ mkdir backup

$ cp thesis/citations.txt thesis/quotations.txt backup

What does cp do when given three or more filenames, as in:

$ ls -F

intro.txt methods.txt survey.txt

$ cp intro.txt methods.txt survey.txt

The command ls -R lists the contents of directories recursively,

i.e., lists their sub-directories, sub-sub-directories, and so on

in alphabetical order at each level.

The command ls -t lists things by time of last change,

with most recently changed files or directories first.

In what order does ls -R -t display things?